On this page:

- Treatment for ovarian cancer

- Who will be looking after you?

- Surgery

- Chemotherapy

- Other drugs and clinical trials

- Making decisions about your treatment

- Your wellbeing

Treatment for ovarian cancer

It’s common to treat ovarian cancer with surgery and chemotherapy (drugs that aim to kill cancer cells). Your treatment will depend on the type of ovarian cancer you have. For example, low grade serous ovarian cancer responds less well to chemotherapy than high grade serous so you may be treated using other drugs. It will also depend on the stage and grade.

You may have:

- surgery before starting chemotherapy, or

- some chemotherapy before surgery and some afterwards. This is called neoadjuvant chemotherapy. You may have this if your treatment team don’t think it will be possible to remove all of the tumour during surgery before shrinking it with chemotherapy. After three or four cycles of chemotherapy, if your scans show that the cancer has shrunk, then you may be able to have surgery.

Sometimes surgery isn’t considered the best option for treating the cancer. This may be if you have a medical condition that means your body will not cope with a big operation. Or it may be that having surgery to remove the cancer would cause too much damage to other organs in your body. In these cases your team may advise that you have chemotherapy on its own.

If the cancer is diagnosed at a very early stage it may be treated just by surgery.

Who will be looking after you?

You will be looked after by a multi-disciplinary team (MDT). This team will involve all the people caring for you. The main hospital staff you'll come across will be:

- Oncologists

- A gynaecological oncology surgeon will do your operation. They have had extra training to operate on those with ovarian cancer. You may also hear them called a surgeon.

- A clinical or medical oncologist organises chemotherapy. Medical oncologists also organise hormonal treatments and targeted treatments such as PARP inhibitors. Clinical oncologists focus more on radiotherapy but also organise chemotherapy.

- Gynae-oncology clinical nurse specialist (CNS)

This is a nurse who has had extra training to look after anyone with gynaecological cancers, including ovarian cancer. In some places CNSs are called specialist gynaecology nurses. In other places they are called Macmillan nurses. You may also hear them called your key worker.

Your CNS should be the person involved in every step of your care and treatment from when you’re first diagnosed. You may have access to one CNS or a team of CNS’s depending on where you live in the UK.

- Chemotherapy nurse

If you’re treated with chemotherapy, a team of chemotherapy nurses will help you through your treatment. They will also help with any side effects that you have.

- Other health professionals

Other health professionals involved in your care may include:

- radiologists – who do scans like x-rays and CT scans

- psychologists – who help your mental health during and after a cancer diagnosis

- pathologists – who look at the cells in a laboratory to see if they are cancerous and to find out what type of cancer it is

- anaesthetists – who choose the right anaesthetic for you when you have surgery. This stops you from feeling pain during the operation. They also help you to prepare and recover from surgery

- dietitians – who give advice about what to eat and drink

- physiotherapists – who help you with movement and exercise

- occupational therapists – who help you cope with daily tasks that are difficult because of illness.

The MDT meet up often to talk about the care and treatment of their patients. They review test results and talk about plans for treatment. Remember that you should also be fully involved in decisions about your treatment.

Who should I speak to if I have questions or problems during treatment?

You should be told who the main person looking after your care and treatment is. This is usually a CNS. You should be given contact details for them so that you can get in touch with any questions or problems.

It’s important that you understand what’s happening to you and why. You may have different key contacts for different parts of your treatment. If you’re not sure who they are, or how to contact them, ask someone in your treatment team to write down the details for you.

Surgery

Dhivya Chandrasekaran, Consultant In Gynaecological Oncology at University College London Hospital explains whether you will need surgery, when you would have it, what to expect from it and how long it will take to recover. Also hear from other women with an ovarian cancer diagnosis who have been through surgery:

- Preparing at home

It’s important to be as fit and healthy as possible for surgery. Eating a well-balanced diet that includes lots of fruit and vegetables can help with this. Staying active can also help. You could try short walks, gardening or doing some exercises in your home. Some NHS hospitals offer prehabilitation programmes. These offer support and advice to help you physically and mentally prepare for cancer treatment.

It's also useful to plan ahead before surgery. Make sure that there’s plenty of food in the house so that you don’t need to worry about going to the shops after. You may also want to consider making sure that everything you might need in the house is within easy reach of your bedroom. Or you might choose to sleep in a different place to be closer to the bathroom while you recover.

Making some small changes can make your recovery easier.

Macmillan has more information about preparing for surgery.

- Before your surgery

At the hospital you will be examined and given some tests to check that you’re well enough to have surgery. Your surgeon will tell you what will happen during the operation. It’s often difficult for the surgeon to know exactly how much surgery you will need until they begin to operate, so they may talk to you about the different possibilities and options.

- What happens during surgery

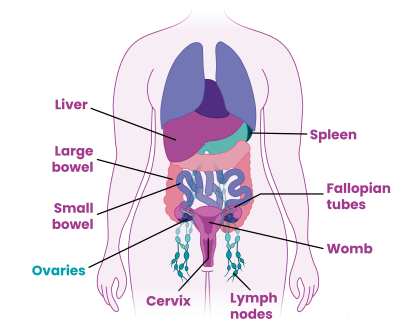

Surgery normally includes removing:

- the womb (uterus)

- the neck of the womb (cervix)

- both ovaries and fallopian tubes (called a salpingo-oophorectomy)

- the omentum (a sheet of fat that hangs within the tummy).

You may have lymph nodes removed as well. These are small structures that are part of your immune system and contain white blood cells. They help your body fight infection and disease. If your surgery included removing sections of the lymphatic system (like lymph nodes) you may be at risk of lymphoedema. There are lots of ways to manage the symptoms of lymphoedema.

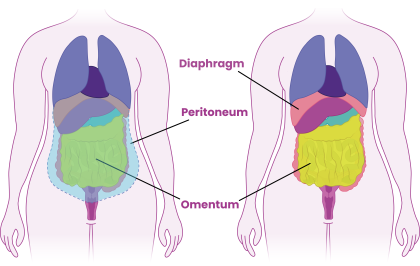

If the ovarian cancer has spread further, you may need surgery on other areas in your body. This may include removing parts of the:

- bowel (an organ that is part of the digestive system and breaks down food)

- diaphragm (a muscle that helps with breathing)

- liver (an organ that helps to absorb nutrients from food and break down toxic substances)

- peritoneum (a large, thin, flexible sheet of tissue that covers the organs inside your tummy)

- spleen (an organ in the upper left side of your tummy that makes up part of your immune system).

Surgery will also confirm the type, subtype, stage and grade of the cancer. For example epithelial, high grade serous, stage 3.

If you’re a younger woman you may have be worried about the impact of surgery on your fertility and coping with early menopause. If you have been diagnosed with early-stage ovarian cancer and the cancer is only in one of your ovaries or fallopian tubes, your surgeon may be able to leave your other unaffected ovary and fallopian tube if you are hoping to have children in future. This is called fertility-sparing surgery.

If you have surgery on the bowel, most of the time the affected part of the bowel can be removed and the two ends put back together again. This is called an anastomosis. But sometimes this isn’t possible or safe and your body will need a new way for your faeces (poo) to be passed. In this situation your surgeon will make an opening through your abdominal wall (tummy) and bring the end of the bowel through it. This is called the creation of a stoma or ostomy.

- After your surgery

Surgery puts your body through a lot of stress, so it’s very important to give yourself time to heal and recover. In the first weeks after your surgery you should take things very gently, allowing yourself plenty of time to rest. Listen to your body as you slowly do more activity. It will tell you how far you can go and what you can take on, depending on how you feel.

You will be given pain medication so that you are as comfortable as possible. After surgery it is common to feel tired as your body is working hard to recover. It is important to build up activities gradually to help you through this. If you’re worried about any side effects, talk to your CNS about how you feel.

You will be given compression stockings to wear. These gently squeeze the legs and will help reduce the risk of blood clots developing in your legs and lungs. You will also be given blood thinning injections for 28 days after surgery to reduce the risk of blood clots. You can reduce this risk more by:

- Making sure you drink enough water (avoiding a lot of caffeinated drinks such as coffee, tea and cola)

- Going for short walks inside the house or outdoors

- Moving your toes when you are sitting or lying down.

Macmillan has more information about recovery from surgery.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells in your body. It’s given through a drip that goes into your veins. This is called an intravenous infusion.

Dr Shibani Nicum, Consultant Medical Oncologist at University College London Cancer Institute explains how chemotherapy works, whether you will need it, when it would start and what to expect. Also hear from other women with a diagnosis of ovarian cancer who have been through chemotherapy:

- What chemotherapy will you have?

Your oncologist will decide with you which chemotherapy drugs you will have. It’s likely you will get a combination of drugs, one of which is a platinum-based chemotherapy. This mix of drugs is usually a drug called carboplatin (but sometimes cisplatin) and a drug called paclitaxel (most commonly called Taxol®). Sometimes carboplatin will be given on its own. This may be if you’re not well enough to cope with the side effects of both drugs, or if you were diagnosed at an early stage.

You will usually have six sessions of chemotherapy in total, each one three weeks apart. This gap is to let your body recover from each session before the next one starts.

Sometimes, if you’re not very well or if you have a lot of side effects from the chemotherapy, your oncologist may decide to give you your chemotherapy in a smaller dose every week. Sometimes your oncologist may need to delay your next chemotherapy session for a week or two. This can happen if your blood counts have not recovered (increased enough) or if you have really bad side effects from the last cycle of chemotherapy.

- What happens when you have chemotherapy treatment?

It’s likely you will have chemotherapy at your local hospital or cancer centre. At the hospital you will have some blood samples taken for testing before each cycle of chemotherapy. These are checks to make sure that it’s safe to go ahead with the treatment.

When you have your treatment, you will be shown into the treatment room where you will be able to settle yourself in a comfy chair. The nurse will place a cannula into one of the veins on your hand or arm and attach a drip so the drugs can enter your bloodstream. A cannula is a small tube like a needle.

The drugs are given over several hours. It might feel a bit uncomfortable as the cannula goes in but shouldn’t be uncomfortable after this. If it does hurt or feel uncomfortable during treatment let the chemotherapy nurse know.

If you’re having carboplatin and paclitaxel then the nurse will give you the paclitaxel first and then carboplatin afterwards.

If it’s difficult for you to have a cannula put into a vein in your hand or arm, you may have a central line put in that stays in place throughout your treatment. A central line is a tube that is placed in a large blood vessel in your chest. It means you will not need a cannula put in your hand or arm for each chemotherapy treatment. There are three types of central line; a PICC line (put in through a vein in the arm), a portacath and a Hickman line (put in through the chest).

You will usually spend most of the day at the hospital so you might want to ask a relative or friend to keep you company, if allowed by your hospital. A couple of magazines, a good book, or watching something on your phone or tablet can also help to pass the time.

- Chemotherapy side effects

It’s common to get some side effects from chemotherapy. These can usually be easily treated. It’s rare for side effects to be severe. Usually, side effects don’t start straight away. When you see the list of all the possible side effects it can be worrying. Remember it’s unlikely that you will experience all of them, they should be mild and your treatment team can help.

One of the effects of chemotherapy is that it reduces the number of white blood cells in your blood. That means you might not be able to fight infections as well as before. This is why the hospital will want you to contact them immediately if you get a temperature or feel ill in the days or weeks following treatment. This can happen at any time, but your blood count is likely to be at its lowest seven to 14 days after chemotherapy. You should avoid people who have infections (viral infection or infections treated with antibiotics). Your hospital should tell you whether you need to limit your contact with other people, but if you have any questions at all about this, ask them.

Your hospital should give you a 24-hour helpline number to ring if you're feeling ill at any time during your chemotherapy and in the weeks after treatment.

Contact your treatment team straight away if you suddenly feel unwell or you have a fever (a body temperature above 37.5°C/99.5°F).

Other common side effects of chemotherapy can include:

- Tiredness and fatigue – most people feel very tired during chemotherapy so it is important to plan time to recover your energy.

- Feeling or being sick – you will be given medication that helps with sickness to take home after your chemotherapy treatment. If you are sick (vomit) or feel nauseous, always let your chemotherapy team know as they may be able to change your medication.

- Hair loss – it’s rare for platinum chemotherapy to cause hair loss. But nearly everyone treated with paclitaxel will experience temporary hair loss. This will usually start two to four weeks after treatment begins. You may be offered scalp cooling. This is a cold hat that you wear while having chemotherapy to help reduce hair loss. Cold caps can be uncomfortable and treatment does take longer when they are used. However, they can work really well, and you can ask for support to make it work for you. You may also want to find out about the free wig service your hospital may offer.

- Tingling or numbness in your hands or feet – chemotherapy can affect your nerves, which may cause your feet or hands to tingle or feel numb. This is known as peripheral neuropathy. Complementary therapies can help with this.

- 'Chemo brain' or 'chemo fog' – this is when you can’t think as clearly after chemotherapy as you did before treatment and usually goes away after a while.

- Changes in taste or eating problems – this is usually temporary but can be difficult if you’re also feeling sick. Read more about eating problems and changes in taste.

Macmillan has a full list of possible chemotherapy side effects.

Many people find that as treatment continues they become used to the side effects and can plan around them. It can be helpful to keep a diary so that you know which side effects to expect and when after each chemotherapy session. Speak to your treatment team if you are experiencing side effects as they can help.

You can also join our Facebook group to talk to others and read their tips for chemotherapy.

Other drugs and clinical trials

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy involves using radiation to treat cancer. This produces beams of high energy to kill cancer cells. It’s not usually used to treat ovarian cancer. In special circumstances your oncologist may suggest radiotherapy, but they will discuss this with you if this is the case.

Targeted drugs

Depending on your individual circumstances, such as the type of tumour and whether surgery is possible, you may be able to have other targeted drugs. The way drugs are approved for use in the NHS differs across the UK which means that there can be some differences in what drugs are available depending on where you live.

Find out which targeted drugs are available across the UK.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are research studies that investigate potential new drugs, new ways of giving treatments or different types of treatments and compare them to the current standard treatments.

Read more about clinical trials – what they are, how they work and how you could get involved.

Making decisions about your treatment

You may want to have a detailed conversations about treatment choices, while others would rather ask their oncologist to recommend an option. You may find yourself caught up in a medical whirlwind, talking with your treatment team about what happens next. Take a moment to think about what you want and make sure you have the information you need to make any decisions or choices put to you.

It can be useful to share your thoughts about the following questions with your oncologist or CNS:

- How much detail do you want to know?

- When do you want this information?

- How do you want to make decisions?

- Do you prefer to take some time to take the information in before deciding?

- Do you need to talk it through with anyone before deciding?

- What is the aim of the treatment?

- Will this treatment cure the cancer?

- Will the treatment control the cancer or control the symptoms?

- Will you need more treatment in the future?

The key decisions

The treatment you have will be a joint decision between you and your treatment team. Key decisions about treatment options include where to have your treatment, when to have surgery, when to have chemotherapy and what type of chemotherapy or other drugs are best for you. Asking some of the following questions may help you decide what you want to do:

- What treatment options are do I have?

- How will certain treatments help me and how effective are they?

- Does the treatment have any risks now and in the future?

- What are the side effects? How might the treatment affect me physically, emotionally and sexually?

- How long do these side effects last?

- What might help me to reduce, control or recover from these side effects?

- How will treatment affect my life and health in general?

- Will I be able to go on holiday?

- Can I continue to work?

- If I stop working, when will I be able to go back to work?

- Where can I be treated?

- Would a different cancer centre offer me other treatment options?

- Is it possible to take part in a clinical trial (a research project) at this centre or any other centre?

Second opinions

After talking to your treatment team about your options you may still feel unsure about what to do. If you would like to get a second opinion, just ask. A second opinion is when you speak to another oncologist or surgeon about your diagnosis and treatment options. Your CNS, hospital doctor or GP should be able to tell you how to do this.